For foreign investors in Bali, the “Banjar” is often a mysterious entity that appears only when money is requested or a road is closed for a ceremony. Many villa owners operate under the mistaken belief that having a government business license (NIB) provides immunity from local customary obligations. This disconnection leads to serious operational friction, from sudden restrictions on guest access to the refusal of essential support during village emergencies.

The agitation peaks when a “voluntary” donation request arrives with a suggested minimum that feels more like a tax than a gift. Without understanding the cultural and operational power of the Banjar, foreign owners often react defensively, viewing these contributions as extortion rather than community investment. This friction can escalate quickly; a villa that is “legally” compliant but culturally isolated may find its trash uncollected, its noise complaints amplified, and its relationship with the neighborhood irretrievably broken.

The solution lies in proactive engagement and clear allocation of Negotiations and Donations to the Local Banjar. Understanding that the Banjar is a legitimate operating stakeholder—responsible for security, infrastructure, and spiritual harmony—changes the dynamic from conflict to partnership. By budgeting for these costs and assigning a culturally competent liaison, you can secure not just permission to operate, but the active protection and support of Bali’s unique community structure that surrounds your investment.

Table of Contents

Defining the Banjar: Adat vs. Dinas Roles

The Banjar is the bedrock of Balinese society, a customary council governing the secular and religious life of a specific neighborhood. While the Indonesian state handles administrative law, the Banjar manages the Adat (customary law).

It is crucial to distinguish between the two heads of leadership: the Kelian Dinas handle administrative matters like census data and waste management, while the Kelian Adat oversees religious ceremonies and customary security (Pecalang).

For a villa owner, the Banjar is effectively your local government, holding the power to approve or block activities that impact the community’s harmony. In 2026, their influence remains paramount.

They control physical access to the village and enforce community standards. Ignoring their role is a strategic error. A villa that integrates well with both the Dinas and Adat leadership gains an invaluable ally, often receiving priority assistance during power outages or security incidents.

Who Pays? Allocating Responsibility Between Owner and Guest

A common point of confusion is whether local customary contributions should be passed on to the guest. Industry standard in Bali dictates that recurring community contributions are an operational expense borne by the business owner, not the short-term tenant. Just as you wouldn’t ask a hotel guest to pay the property tax, you should not ask a holidaymaker to pay the monthly Banjar dues.

However, specific costs related to guest activities—such as a wedding, a large party, or a commercial photo shoot—are pass-through expenses. If a guest wishes to host an event that requires Pecalang (local security) or extra parking management, these fees should be quoted transparently in the booking contract and paid by the guest. Clarifying this distinction in your Terms & Conditions prevents awkward conversations at check-in and ensures the Banjar receives its dues without delay.

The Role of the Local Representative in Negotiations

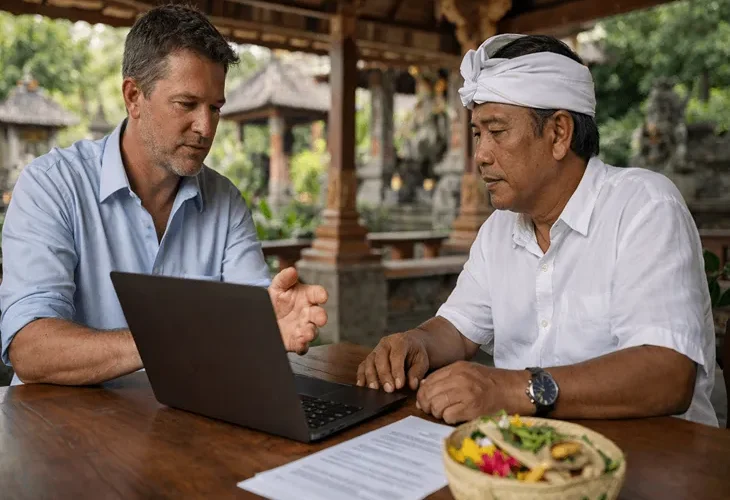

Direct negotiation between a foreign owner and the village leadership often leads to misunderstandings due to language barriers and cultural nuances. The most effective approach is to appoint a local representative—typically your villa manager or an established villa management firm—to act as the bridge. This liaison understands the subtle etiquette of Basa Bali (Balinese language) and knows when to approach the Kelian Adat versus the Kelian Dinas.

Your representative’s role is to formally introduce the business to the community, explain the operational model, and agree on a fair monthly contribution. They act as a buffer, filtering minor community requests while escalating critical issues to you with context. Trusting a local expert to handle Adat leadership mediation ensures that the agreed amounts are consistent with local standards, preventing you from being overcharged as a “wealthy foreigner” while ensuring the village feels respected.

Types of Contributions: Sumbangan Wajib vs. Event Fees

Financial obligations to the Banjar generally fall into three categories. First are the Monthly Dues, often formally documented as Sumbangan Wajib (Mandatory Contributions). While foreigners often view these as “voluntary,” for a business, they are a fixed operational cost covering trash collection, street lighting, and general security. For a commercial villa, this typically ranges from IDR 100,000 to IDR 500,000 per month and should be paid promptly.

Second are Event Fees. Any activity disrupting the neighborhood’s quiet enjoyment—loud music, extra traffic, or drone usage—requires a specific permit and fee. These are transactional and scalable; a small dinner party might incur a nominal fee for parking help, while a 100-person wedding will require a substantial contribution to the temple fund and wages for the Pecalang. Failing to secure these permits can lead to the Banjar shutting down your event mid-celebration.

(Disclaimer: Amounts may be changed at any time without prior notice by the authorized authority.)

The "Dana Punia" Etiquette for Major Ceremonies

Beyond fixed fees, there is the concept of Dana Punia—voluntary donations for religious or community needs. When the local temple holds a major Odalan (anniversary ceremony) or the Banjar renovates its meeting hall, local businesses are expected to contribute. While technically voluntary, these contributions are a barometer of your social standing. A villa that profits from the beauty of the village is expected to give back to maintain that beauty.

There is no fixed rate sheet for Dana Punia, which makes it a source of anxiety for foreigners. The key is proportionality. A large, high-occupancy villa should contribute more than a small private house. Your local representative can advise on an appropriate amount that signals respect without setting an unsustainable precedent. Viewing this socio-spiritual operational funding as “Goodwill Insurance” rather than a tax helps reframe the expense as a positive investment in your business’s longevity.

Real Story: Turning a Banjar Conflict into a Partnership

Emma, a Canadian investor, had a vision for her Pererenan villa: 100% ROI and zero “unnecessary” expenses. When the Kelian Adat (village head) requested a donation for the temple’s Ngerebong ceremony, she refused, citing her corporate tax filings. She thought she was being a savvy businesswoman.

The village didn’t argue; they simply became invisible. Her trash sat in the humidity, attracting flies. When a guest’s scooter was stolen from the driveway, Emma found the local Pecalang (security) suddenly “too busy” to assist. She was a legal resident, but a social ghost. The stress of the “silent treatment” from her neighbors was more exhausting than any tax audit.

Emma realized that in Bali, the Banjar is the heart of the business. She engaged a professional manager to organize a Simakrama—a formal meeting. She arrived with an offering and a sincere apology, acknowledging that her villa benefited from the very ceremonies she had refused to support. She made a retroactive Dana Punia (donation) to the village hall.

The atmosphere shifted instantly. The Pecalang didn’t just find the scooter; they began including her villa in their nightly patrols. “I thought I was saving $200,” Emma says. “But I was actually losing the soul of my neighborhood. Now, I don’t see Banjar fees as an expense; I see them as the price of belonging.”

Consequences of Ignoring Customary Obligations

The risks of bypassing the Banjar extend far beyond social awkwardness. In Bali, the Banjar has the authority to enforce Awig-Awig (customary laws). If a villa is deemed a nuisance—due to noise, disrespect, or refusal to contribute—the Banjar can impose sanctions. These range from fines to physical blockades of the property entrance during ceremonies. In extreme cases, a Banjar can petition the district government to revoke a business license, citing community disruption.

Operationally, a hostile relationship with the Banjar makes daily life difficult. Staff may be pressured by their own community to quit, suppliers may be blocked from entering the street, and guests may face hostility. No amount of legal paperwork can compel a community to accept a business they despise. Respecting the village community engagement process is the only viable path to operational stability.

Best Practices for Long-Term Community Harmony in Bali

To maintain a healthy relationship, transparency is key. Keep the Banjar informed of any changes in your operation, such as renovations. If you plan a renovation, introduce the contractor to the Kelian Dinas beforehand to discuss logistics. Additionally, acknowledge the vital role of the Pecalang, especially during Nyepi. In 2026, their authority includes monitoring digital silence and light emissions; your Banjar contributions fund this enforcement, ensuring your guests don’t accidentally violate serious customary laws.

Additionally, consider non-monetary contributions. Offering your villa as a venue for a small community meeting, sponsoring the local youth group’s football uniforms, or simply providing coffee and snacks for the Pecalang on duty goes a long way. These gestures humanize your business. When the village sees you as a neighbor rather than just an ATM, negotiations become friendlier, and donations become a shared effort to improve the neighborhood you both call home.

FAQs about Banjar Fees

While not a state tax, they are obligatory under customary law (Adat). For businesses, they are often classified as Sumbangan Wajib (Mandatory Contributions), and refusing to pay leads to social sanctions.

For a standard 3-bedroom commercial villa, budget between IDR 150,000 and IDR 300,000 per month. This varies significantly by location (e.g., Seminyak vs. Tabanan).

Yes, but it should be done respectfully through your local representative (manager). Explain your current occupancy or business situation. It is better to give a smaller, sincere amount than to refuse outright.

If the party involves loud music, outside guests, or late hours, yes. It is safer to inform the Kelian Adat and pay a small permit fee than to have the Pecalang shut it down.

This must be specified in the lease. Typically, for a yearly rental, the tenant pays the monthly dues. However, for a leasehold investment, the owner retains responsibility for major Dana Punia donations.

You may face "social sanctions," such as uncollected trash, lack of security support, or even restricted access to your property during village events.